Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

On October 23, 2022, Jim Henterly sat on the passenger bench of a National Park Service AStar helicopter, peering out at the craggy expanse of North Cascades National Park. Next to him was a firefighter from the NOCA (North Cascades) wildland crew, and directly in front of them stood 6,102-foot Desolation Peak. It was an unorthodox move for the parks system to allow the helicopter into the backcountry, but a moderately active fire that had broken out late in the season near Ross Lake, less than 2 miles downhill from Desolation Peak, had closed the trails. On the summit, a cabin covered in silver tinfoil glimmered in the sun like a wrapped Christmas present in a sea of craggy peaks. The first dusting of snow that patched the ground and frosted the roof added to the impression.

It had been a month since Henterly, the resident fire lookout on Desolation, left for the season, unable to properly close the lookout cabin for the winter because of the ongoing wildfire activity. After his lookout season ended in September and he went home to Whatcom county, Henterly didn’t know if he’d return before the following June. But the Desolation Fire, as it became known, climbed halfway uphill toward the lookout cabin, threatening to burn it down. In an effort to preserve it, fire crews had wrapped the 14 ½ by 14 ½-foot wooden structure in a foil blanket. And now, with the threat of the fire passed, Jim returned to remove the foil, inspect the structure, and prepare it for the heavy snows of a North Cascades winter.

To his relief, Henterly, who has spent seven seasons scanning for smoke atop Desolation, found no damage to the lookout cabin or any of its equipment. The structure itself has stood atop Desolation for almost a century, but this latest fire isn’t the only thing that threatens its continued existence as the last staffed fire lookout in North Cascades National Park.

The summer before, I spent some time with Henterly at Desolation, which is also one of the few remaining staffed lookouts in the entire state of Washington. After corresponding by email for months, I met him at the tail end of the season. After a rigorous 5-mile hike with nearly 5,000 feet of elevation gain, I made it to the ridgeline and got my first glimpse of the cabin. With the shutters propped up, the structure gave me the impression of a single-story pagoda, symbolism that added to my reverence of this place. A man with deeply kind eyes and the svelte body of a lifelong hiker in his sixties, Henterly was cleaning the cabin and readying it for winter when I arrived. A big storm was forecast to sweep into the region within days and the shutters of the mostly glass structure would need to be fastened.

The Desolation Peak fire lookout stands about a foot off the ground on cinder blocks, in the foreground of the twin-fanged peaks of Mt. Hozomeen. The box-like building is painted a light shade called “lookout gray,” and its shutters are raised during fire season to reveal windows on all sides. The interior of the small cabin is a calming green called “Irish meadows,” which, like the exterior color, the Forest Service used regularly for lookouts and the National Park Service maintains for historical continuity. Against the four walls are a lone cot, a desk with an ancient hand-crank coffee grinder, and a bookshelf. In the center of the room sits the Osborne Fire Finder, a device that resembles a high circular table with sights and a map, and can give ranges and bearings from any location within view. Its purpose is to pinpoint smoke and flames so that the operator can dispatch wildland firefighting crews to the blaze’s exact location.

As he went about stowing objects under the cabin, Henterly told me how he trained as a wildland firefighter and fire lookout for over 20 years to get this post. Some years standing watch as a lookout can be slow with very little fire activity, but these last few years have mirrored the amplified wildfire season that the rest of the West has experienced. Henterly told me about a fire a few years back that holds special significance to him, and he showed me how he used the Osborne Fire Finder to acquire the location by lining up the sights of two apertures that rotate around the map. That fire was classified a monitor-only situation because it was in the remote wilderness of the Arctic Creek drainage north of Mt. Prophet. On his small desk was the Very High Frequency (VHF) radio he used to call in the coordinates and updates to headquarters. Henterly’s job was to observe, document, and relay the life of the flame. Because he found it, the Fire Management Office designated it the Arctic Jim Fire.

Built in 1932, this lookout tower near the border of Washington and British Columbia has long stood as a symbol of firefighting in the West. A century atop a mountain has given this structure a character all its own, with remnants from previous tenants ranging from books and cups to maps and memorabilia. From the outside, it’s the only man-made object in sight, aside from an outhouse a few yards beyond. It’s not surprising that it has captured the imaginations of backpackers, writers, and historians for decades.

Jack Kerouac was the first to introduce me to fire lookouts through his novels Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, both of which chronicled his experience as a fire lookout on Desolation in the summer of 1956. Notable nature writers Gary Snyder, Norman Maclean, Edward Abbey, and Phillip Connors have also written about the monk-like experience of living in a glass house on a mountaintop. These stories drew me to visit the historic Desolation Peak Lookout 13 years ago, and I’ve revisited the site a handful of times since, along with countless other lookouts across the region.

According to the Forest Fire Lookout Association (FFLA), fire lookouts proliferated between 1930 and 1950, when the Forest Service maintained more than 5,000 towers around the country, mostly concentrated in the forests of the western United States. During this era, Washington alone built 660 alpine lookouts. Since the 1950s, government agencies have torn down many of these lookouts due to disrepair or destruction in forest fires. A number of nonprofit preservation groups like the FFLA maintain some of the remaining structures for public enjoyment.

In a 2019 survey, the FFLA estimated that only around 300 lookout towers were still staffed in the United States, mostly by volunteers, and those small numbers continue to dwindle due to advances in technology. With the use of drones, satellites, aircraft, and even fixed camera systems, the role of fire lookout is quickly becoming obsolete. In Washington, only 93 lookout towers remain, and only a third of those ever host an actual person. Of these few, only a handful are paid, part-time positions within the National Park or National Forest services during any given fire season, which is usually between June and September. The heightened fire activity in the West has not led to higher staffing levels of fire lookouts. Not yet.

Henterly tells me a pivotal role of the lookout at Desolation is to relay radio messages from field crews to headquarters in the park. These radio dispatches, pertaining to ongoing wildfires, trail work, and even rescues, are too far away for headquarters to pick up. Jim constantly monitors every word that comes out of his handheld. It could be a firefighter Mayday, or a mishap that needs to be passed on. Every evening he relays his own report to HQ.

During the 2022 lookout season, Jim proved the importance of his work and the value of fire lookouts in general. During the height of the fire season, he monitored and reported on approximately 20 different wildfires, not only within North Cascades National Park, but also in the neighboring Pasayten Wilderness and in Canada. His dispatches provided critical information to fire crews and a low-cost alternative to the exorbitant financial costs of reconnaissance flights. Those flights are intermittent, and Jim’s constant attention, coupled with regular radio reports, provides vital information with little overhead. The work that Jim does, and the necessity of Desolation Lookout, is so vital that fire crews hiked to the peak last fall to wrap it in protective foil, so that its mission may continue in the future. With the growing fire seasons created by climate change, it seems that lookouts are more important than ever. Perhaps Jim and Desolation Lookout will inspire government agencies to invest, one more time, in the tried and true method of fighting fire by posting fire watchers to stand guard against our burning world.

Meanwhile, the few remaining towers are garnering huge interest from outdoor enthusiasts, perhaps due to the fact that the role of the fire lookout is slowly fading into history. Backpackers can rent many of these structures overnight. Some are open to the public on a first-come, first-serve basis and are often crammed full of campers during the height of summer. These communal barracks are especially sought-after for Pacific Northwest hikers, who ascend steep mountain terrain in droves for a chance to sleep protected amongst the high peaks. Regional blogs keep track of what lookouts are available to rent, which ones are free to stay in, and log the currently staffed locations, so visitors can hike to the cabins themselves and hear first-hand what it’s like to be a fire lookout.

The lives of lookout personnel require patience uncommon in our time, distilled with enduring focus. Every minute or so during my visit, Henterly returned his gaze to 360-degree scans of the surrounding landscape, stalling our conversation and creating stretches of silence that punctuated his stories. Much of the fire season has no sign of smoke, so his vigil can become endlessly repetitive. Luckily for Henterly, his view is inspiring. There are mountains on all sides, spreading out in ripples of ridgelines and glaciated peaks that comprise the northern expanse of the Cascade mountains.

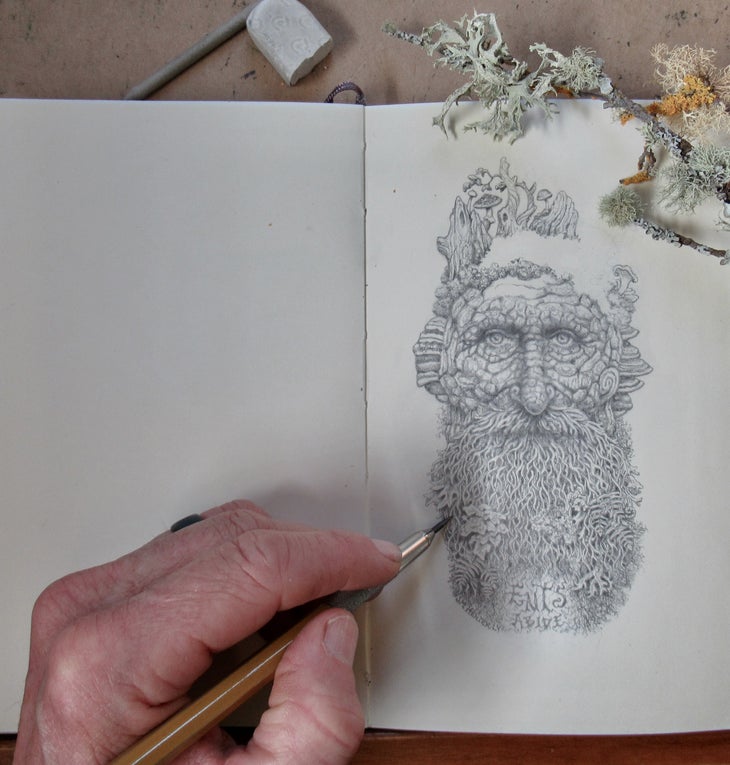

It’s useful for lookouts to have personal interests to fill the quiet moments. For Henterly, drawing is a way to while away the daylight. With a pencil, he sketches finely detailed pictures that can fit into the palm of your hand. He’s drawn portraits of nature writers and mythical creatures, such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s ents, which are enormous walking and talking trees. The sketches merge with his lookout tasks, as the contrast of light smoke on a dark landscape parallel the lead on white paper. Over the seasons, he’s turned his sketches into stickers that he’s posted around the cabin with quotes from his favorite authors.

On the doorpost, I noticed a sticker Henterly drew with John Muir’s quote, “One can make a day of any size.” It’s a fitting adage for a fire lookout. Because Henterly’s been lucky to staff this lookout for consecutive seasons, he’s grown familiar with this corner of the backcountry. He’s watched a black bear become a mother, guiding her cub through the blueberry bushes until it was finally big enough to venture out on its own. There are also two large ravens that perch on the rooftop of his cabin, and they too welcomed offspring to their avian family. Last year their chick went missing. Henterly recalled the peregrine falcon and Cooper’s hawk that preyed upon the ravens in previous seasons. He hoped the young raven went off on its own, like the young bear.

While the animals have become Henterly’s closest community, there are regular pilgrims, like me, that come to visit the lookout. After so much time alone, Henterly welcomes the opportunity to talk with other humans face-to-face. In these dwindling days of staffed lookouts, Henterly has become a storyteller, sharing the deep history of this place with people who have traveled from all over the world. He told me how Native Americans quarried stones for tools from this ridge for at least 9,000 years. In 1859, a Swiss topographer named Henry Custer explored the area with Native guides and created maps from their journeys. Early U.S. Forest rangers and firefighters, like Ed Pulaski, fought and sometimes gave their lives to protect the land. Trail crews, volunteering their time, maintain the trail and the lookout. Fire crews treasure it as an icon. A long line of lookouts has staffed this peak, including Jack Kerouac, with his vision of a coming generation of backpackers heading into the wilderness.

I noticed a quote by Barry Lopez on the cabin wall: “One of the great dreams of man must be to find some place between the extremes of nature and civilization where it is possible to live without regret.” That ignited a conversation with Henterly about the important work of environmental authors, Lopez and Gary Snyder, Thoreau and Emerson. Talking to Henterly, I felt blissfully lost. I had dreamt of this place for so long, and now I had experienced it personally, making it a small part of my own story. But I didn’t want to outstay my welcome, so I thanked Henterly for his hospitality and slowly began the trek to my campsite at the southern tip of Starvation Ridge. Henterly walked with me along the alpine meadow. We stopped to scan for the young black bear, and he invited me to return in the morning for a cup of black coffee and more talk of our shared interests.

Back at my camp, more than 15 miles in any direction from the nearest road, I watched the dark of the night unfurl like a blanket over Starvation Ridge as pinpricks of stars poked through the sky. My eyelids grew heavy. There on that primeval post, one of the last of the fire watchers stood guard against the elements. Though I couldn’t see the lookout from my campsite, I imagined the lone light of the tower burning like a lantern in a sea of darkened peaks. It’s been burning in my mind these past years, a beacon of inspiration that draws backpacking pilgrims like me to this vast wilderness. Its light will burn longer still: In June 2023, Jim Henterly will begin his eighth consecutive season as Desolation Peak’s fire lookout.

From 2023